I love growing my own vegetable plants from seed. It’s a bit magical given that inside each small, nondescript seed lies the makings of something grand – perhaps a 200-pound pumpkin or bushels of tomatoes!

Starting vegetables from seed is both a science and an art. And although it is relatively easy to do, there are a few common pitfalls that can hinder successful seed germination. By understanding basic seed biology and the germination process, you can become more successful at seed starting and most importantly, avoid failures.

Seeds Are Alive!

Seeds may appear brittle and lifeless, but they are very much alive. Inside the seed’s outer shell lies the endosperm, which is packed full of the fats, carbohydrates, and proteins necessary for germination. These nutrients will also sustain the seedling through the early stages of growth.

A seed will remain dormant until it is exposed to just the right conditions for germination and when stored correctly, it can remain viable for many years.

Seed Biology and the Germination Process

Seed germination may seem magical, but in reality, five fundamental conditions must be met for success. These include:

- Moisture: The soil must be moist enough to allow the seed to take in water and break dormancy.

- Temperature: The soil needs to be in the optimal germination temperature range for the specific seed to germinate.

- Oxygen: Oxygen must be present within the soil for seed respiration.

- Light (or the absence of it): Some seeds require light for germination, while others need darkness.

- Seed to Soil Contact: A seed needs soil contact to take up water.

Once planted in the soil, the first stage of seed germination or imbibitation, begins. The seed begins to absorb moisture from the soil. Water is necessary to break seed dormancy and causes the seed to soften and swell. Water also stimulates or “wakes up” the metabolic processes within the seed.

The next stage is the interim, where the seed begins to metabolize stored nutrients, takes in oxygen from the soil (respiration), and begins to absorb light. It’s all in preparation for the final phase of actual germination and emergence.

In the germination phase, visible signs begin to occur under the soil. The first single root, called the radicle root, emerges from the endosperm and burrows into the soil. The radicle is critical for water uptake from the soil and serves to anchor the seedling.

As the radicle burrows into the soil, the hypocotyl, or infant stem, begins to emerge from the seed coat. The “hook-shaped” hypocotyl slowly begins to rise backwards through the soil.

This “hook” serves to protect the forming leaves as the hypocotyl breaks the soil surface and stretches towards light. With emergence achieved, the germination process is complete.

The entire process can take anywhere from two to 21 days or more, depending on the type of plant and the conditions in which the seed was sown. On average, germination takes about seven to ten days from sowing.

So, while it may seem as if there is no activity occurring in your recently sown seed trays, rest assured that there is much going on just below the soil surface!

Why Seeds Fail to Germinate

Seeds need the right moisture, heat, air, light, and soil contact to successfully germinate. If any of these fundamental conditions aren’t met, then germination may not occur or may be significantly delayed. But there are also other factors that can hinder successful germination.

Failure to Break Dormancy

For germination to occur, a seed needs to break its dormancy. For most seeds, this occurs simply from the moisture present within the soil. However, some seeds have special conditions that prevent premature germination thus ensuring survival.

These seeds are known as physically or chemically dormant, and when started indoors they may require additional effort on our part to break dormancy.

Seeds with hard, thick seed coats may be physically dormant. In order to break dormancy, their protective shells need to be breached in some way. In nature, these seeds may break dormancy after by being ingested by a bird or animal. The acid in the animal’s stomach breaks down the seed coat and breaks dormancy. Alternatively, the seed coat can be worn down by friction from wind-to-soil contact.

When started indoors, the tough shells of peas, beans, spinach, and nasturtiums may have difficulty taking up enough water from the soil to break dormancy. To remedy this, hard-shelled seeds are often soaked for a period of time to help soften the seed before planting.

Another method to break dormancy is called scarification. Like friction caused in nature, this process entails scratching the seed surface to thin the tough shell, thus allowing water to penetrate more easily. A piece of sandpaper or a nail file are handy tools for this process, but use caution to avoid damaging the endosperm.

Seeds that are chemically dormant contain the hormone abscisic acid, which inhibits germination until conditions are just right. Rosemary and perennial flowers like coneflower and milkweed are good examples of chemically dormant seed.

In nature, these seeds will lie dormant until they have been exposed to an extended period of cold, wet conditions. The abscisic acid gradually breaks down over time allowing the seed to germinate in the spring. The process of exposure to cold-wet conditions is called stratification.

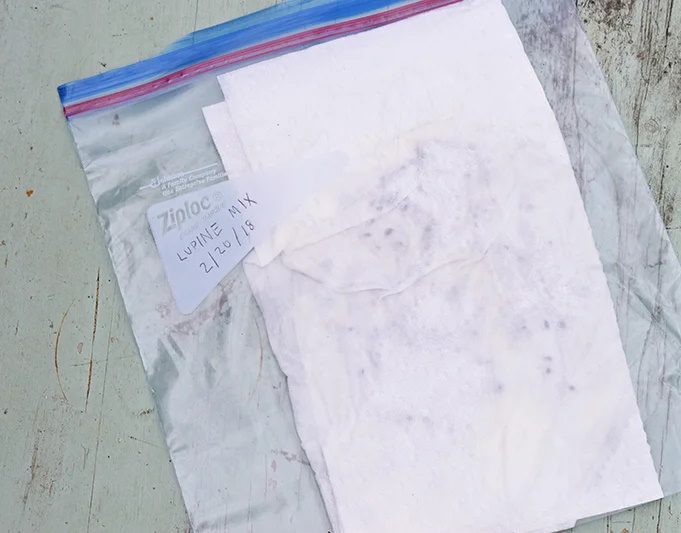

For chemically dormant seeds started indoors, stratification can be achieved by placing seeds in a refrigerator for up to 8 weeks prior to the planting date (length of time may vary depending on the seed variety).

Once removed from the cold confines of the fridge the seed will be ready to plant. Without stratification (naturally or artificially) a chemically dormant seed is unlikely to germinate.

Soil That’s Too Dry or Wet

Proper watering is one of the most critical and trickiest parts of seed starting. If the soil is too dry or wet, germination can fail.

Soil moisture is measured by field capacity, which is the amount of water in the soil when the soil is fully saturated (no water is draining out). The correct moisture level for seed starting is between 50 and 70 percent of field capacity, which for us home gardeners equate to soil that is moist like a damp sponge.

Seed sown into soil that is too dry or that dries out during the germination process will fail to germinate.

Conversely, if there is too much water in the soil, oxygen is pushed out causing the seeds to essentially drown and rot.

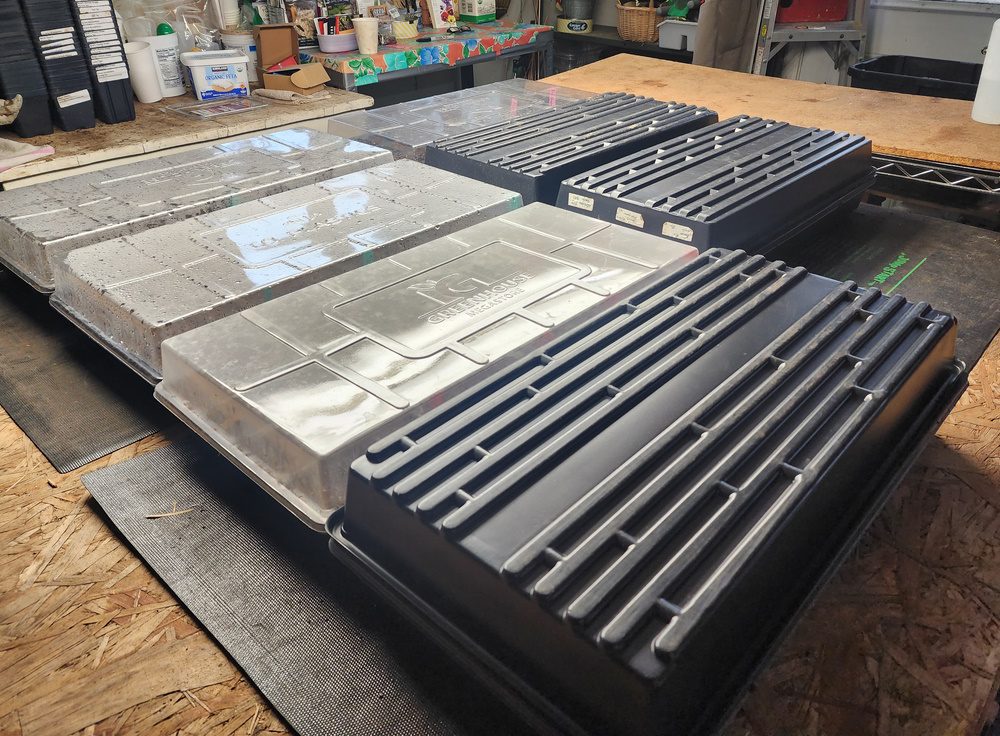

In addition to the amount of water provided, there are other factors that can affect soil moisture. Propagation mats and grow lights can cause soil to dry quickly, whereas and the use of humidity domes can create more moisture within the soil. While these tools aid in successful germination, soil moisture and seedlings need to be monitored carefully when they are in use.

Soil That is Too Cool or Warm for Germination

All seeds have an optimal germination temperature and range, and these vary greatly depending on the specific plant. When a seed is sown at its optimal temperature, germination occurs quickly.

If the soil temperature is below or above the seed’s specific temperature range, it will become thermo-dormant, meaning germination will be inhibited or fail.

Two examples of plants that have specific soil temperature requirements are lettuce and tomatoes. Lettuce, a cool-season crop, has a germination temperature range between 32- and 80-degrees Fahrenheit; its optimal temperature for germination is between 65- to 75-degrees. If the soil temperature is over 80-degrees, lettuce is unlikely to germinate. For this reason, lettuce is typically not sown in the middle of summer.

Tomatoes are a warm-season crop and have vastly different temperature requirements. Their germination temperature range is between 50- and 95-degrees Fahrenheit with an optimal germination temperature between 65- and 85-degrees.

Fortunately, the majority of garden vegetable seed germinates in soil that is between 65- and 70-degrees; a temperature that is easily attained for indoor seed starting.

Download the Seed Germination Optimal Soil Temperature chart here.

Light, Seed Depth, and Germination

While all seedlings need light once they have emerged from the soil, most seeds do not need light to germinate. However, some seed germination is stimulated by light or the absence of it. These seeds are known as photoblastic seed.

When a seed requires light for germination, it is known to be positively photoblastic. Lettuce seed requires light for germination and therefore it is sown on to of the soil with little to no soil covering the seed. If lettuce is planted too deep within the soil it won‘t receive enough light and germination will likely fail.

Seeds whose germination is inhibited by light are known as negatively photoblastic. Seeds like as fennel and a few in the allium family (chives and leeks), require darkness to germinate. It’s important to sow these seeds at the correct depth as well; if they are sown too shallow germination will fail.

Most seeds are non-photoblastic, which simply means they will germinate with or without the presence of light.

Regardless of the seed’s photoblastic characteristics, sowing seed at the correct depth is very important for germination. If a seed is planted too deep in the soil, it can use up all its energy reserves before it reaches the surface and will perish.

Make certain to review the seed packet prior to sowing for light requirements and planting depth. If this information is not on the packet, most seed companies have growing information online.

Using the Wrong Soil

Germination issues can also occur when the wrong soil medium is used for starting seeds. You may be tempted to gather soil from your garden to use for indoor seed starting, but that would be a grave mistake.

Outdoor soil is too heavy and dense and it will compact in small growing cells thus eliminating the space for air circulation. Soil from your garden also carries the risk of disease pathogens that can harm seeds or seedlings.

For the best results, a quality “seed starting” or “germination” medium should be used. These products are also called soil-less mixtures because they don’t contain any “soil.”

Commercial seed starting medium usually consists of finely screened sphagnum peat, wood fines, or coconut coir, plus vermiculite and perlite. The texture is very light and fluffy, so there is plenty of space for air and water, but it also drains well.

Regular potting soil tends to be too coarse and holds too much moisture for seeds. In addition, many potting soils contain fertilizers that young seedlings don’t require – remember, the seed’s endosperm provides everything needed for germination and the early growth of the seedling.

Non-viable Seed

Finally, seed may fail to germinate because it was just a “bad seed.” This could be from age – all seeds eventually lose viability – or it could be from seeds stored incorrectly.

When stored in a cool, dry environment, most garden seed will remain viable for up to 6 years or more depending on the variety.

Commercial seed companies are required to include a “year-packed” date on the seed packet. This ensures fresh seed and helps you keep track of the seed’s age. If you’ve been gardening for any amount of time, you’re likely to have several half-used seed packets laying around.

This is where knowing a seed’s longevity and practicing proper seed storage come into play. For example, when tomato seeds are stored properly, they can remain viable for about 6 years or more. Whereas many seeds in the allium family (onion, chives, leeks) are only viable for a year or so.

Seeds stored in a cool, dry environment have the best chance of remaining viable. Avoid storing your seeds in an area of high humidity or extreme heat – they will expire much more quickly.

If you are uncertain about the quality or viability of your seed, as simple germination test will save you time and money. The last thing you want is to put effort into seed that is no longer viable.

While it may take you a bit of trial and error to master seed starting, the journey is extremely rewarding. I can share from experience, nothing compares to harvesting a juicy, ripe tomato from a plant you grew from a tiny seed!

Leave a Reply