Starting garden vegetables and flowers from seed is relatively easy, and most seeds don’t need any special treatment to germinate. Just plant them in the proper environment and off they’ll grow!

For successful germination, all seeds require the following basic elements:

- Proper soil temperature

- Adequate soil moisture

- Oxygen in the soil structure

- Good seed-to-soil contact

- The presence or absence of light

However, some seeds require a little extra attention to get them started. Sometimes these seeds get a bad rap from gardeners (I’m looking at you, rosemary), because they are difficult to germinate or completely fail to germinate.

With a little understanding of their various special needs and know-how of breaking seed dormancy, we can achieve the successful germination of these so-called difficult seeds.

Photoblastic Seeds: Light’s Role in Germination

Once seeds have germinated, all seedlings need light to grow and thrive. Light is critical to plant photosynthesis; the process of synthesizing food from carbon dioxide and water.

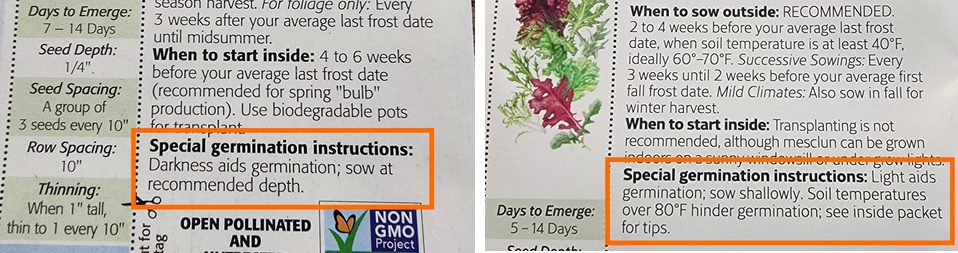

But light requirements for seed germination is very different, and in some cases, very specific for certain types of seeds. When light, or the absence of it, influences seed germination, the seeds are known as photoblastic.

If a seed requires light to germinate, it is positively photoblastic. If positively photoblastic seed is sown too deep into the soil, it will remain dormant and fail to germinate. For germination to occur, these seeds need to be sown on the surface of the soil. A common garden vegetable seed that requires light to germinate is lettuce.

Lettuce seeds are typically sown on the soil’s surface with only very light dusting of soil to cover the seed. Other examples include various grasses (including lawn grass) and tobacco.

While most seed will germinate in darkness, some seed require darkness for germination to happen. These are known as negatively photoblastic seed. For successful germination, these seeds need to be sown at the recommended planting depth or they will also remain dormant.

Examples include many seed in the Allium family, such as onions, shallots, leeks, and chives. Because these seeds are often sown shallowly, placing a dark cover over the seed tray to block light during germination will improve the success rate.

Thankfully, the majority of vegetable and flower seeds grown in our gardens are non-photoblastic, which means their germination isn’t influenced by light and they can be sown in light or dark conditions. Check the seed packet for special sowing requirements related to light and if it isn’t listed, check online.

Chemical and Physical Seed Dormancy

All seeds are living things, but remain dormant until germination conditions are just right for that particular seed. And, those conditions vary, causing frustration to the gardener when germination fails.

There are seeds that require an extended period of time in cold, damp conditions before germinating. Seeds in this category are known to be chemically dormant.

Others have a very hard seed coat that requires a natural abrasion to occur before germinating (like passing through an animal’s intestine). These seeds are physically dormant. Both types of dormancies are nature’s way of ensuring that the seeds will germinate at the right time.

Unfortunately, the right time for the seed isn’t always the right time for gardeners. But thankfully, there are ways we can coerce nature into breaking seed dormancy.

Chemically Dormant Seed

As mentioned, chemically dormant seed requires a lengthy period of cold, moist weather to break dormancy. These seeds produce a hormone that inhibits germination and prevents it from sprouting too soon. Many native perennials and flowers are chemically dormant, including coneflowers (Echinacea), milkweed, lupines, pansies and violas, and my personal nemesis, the herb, rosemary.

In nature, coneflowers will set seed in late summer and early fall. However, the seed doesn’t immediately begin to germinate once it hits the garden soil because the timing isn’t right. This is where nature steps in with chemical dormancy to inhibit germination. It will take an extended period of cold and moisture before the seed will break dormancy (such as overwintering in the garden).

With that in mind, it makes sense to direct sow coneflower seeds in the fall and allow them to overwinter and break dormancy in the spring. Seeds planted in the spring may just lay about, dormant in the garden bed.

Overcoming Chemical Dormancy with Stratification

Of course, as gardeners, we often have our own planting timeline. So, if you can’t wait for seeds to overwinter, or you’ve forgotten to plan ahead, you can mimic the cold, wet cycle of winter and break chemical dormancy with a process called stratification.

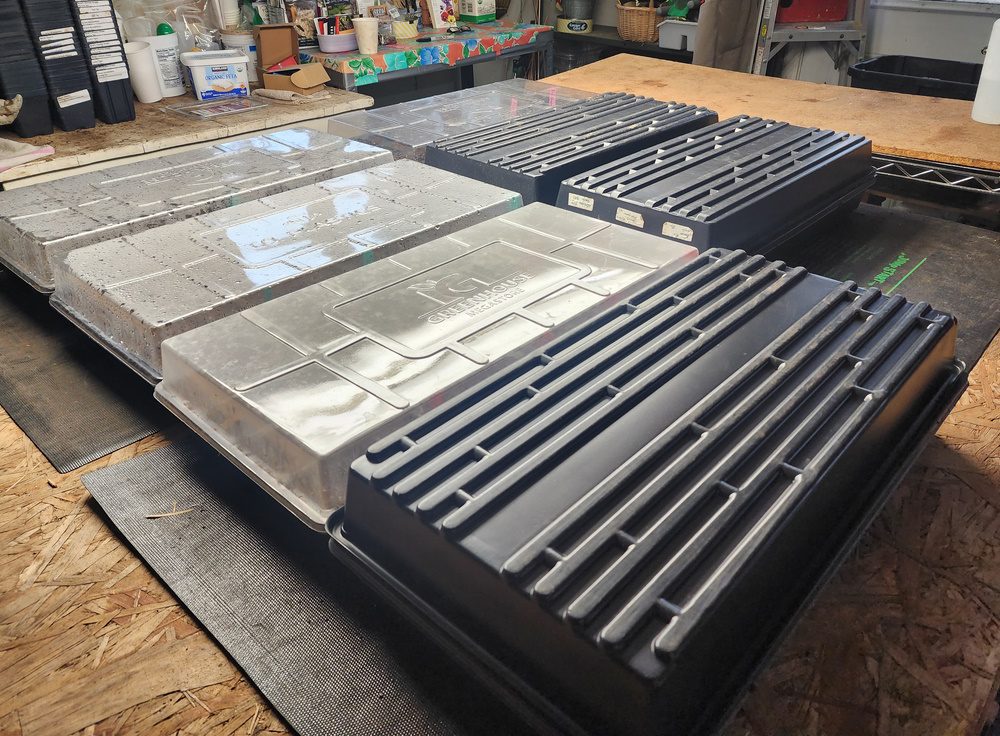

Seeds can be placed in a refrigerator for 4 to 8 weeks to simulate the natural process. Some seeds may need more or less time, so it’s best do a little research on the seed’s specific requirements before beginning the process.

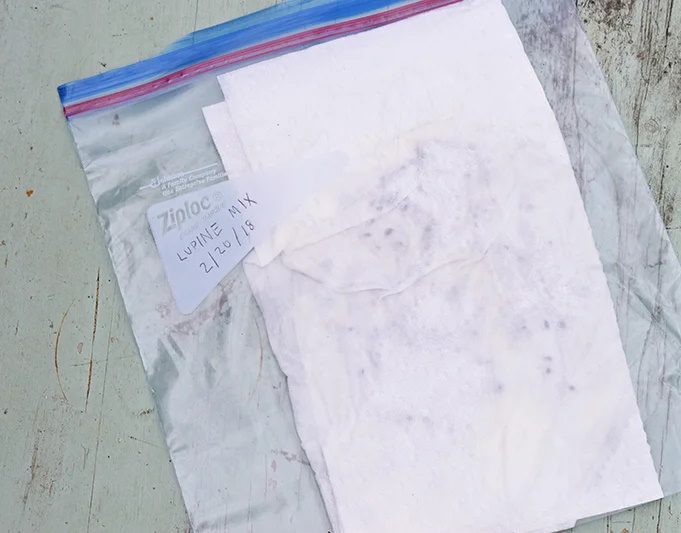

Place seeds in a damp paper towel or in a small amount of moistened seed starting medium (vermiculite or perlite) inside of a plastic zip bag. Don’t seal the bag completely, as the seeds need cold air and moisture for the process to be successful.

Check the seeds weekly to make sure there is moisture in the bag, but not overly wet. Once the seeds go through their faux-overwintering, the dormancy will be broken and they will happily germinate once sown.

Physically Dormant Seed

Another seed type that needs a little extra attention for successful germination are those that are physically dormant. These seeds often have a very hard or thick seed coat that prevents water from reaching the seed embryo. Again, this is a way for nature to protect the seed from germinating before it’s time.

In nature, these seeds may be worn down by soil abrasion from the wind or they will have often traveled through the digestive system of an animal, where stomach acids have weakened the seed coat.

Common garden plants that produce physically dormant seed are peas and sweet peas, beans, spinach, and nasturtiums.

Overcoming Physical Dormancy with Scarification

The method of breaking physical dormancy is called scarification. Scarification is a simple method of manually weakening the seed coat to allow moisture to penetrate into the embryo. An alternative to scarification is soaking the seed to soften the seed coat.

Seeds with thick coats can be gently rubbed on a nail file or a piece of sandpaper to thin the seed coat enough to allow water to penetrate it. Be very careful not to overdo it, or you risk damaging the embryo. It usually only takes a scrape or two to thin the outer shell.

Hard seeds can also be soaked in warm water for up to 8 to 12 hours or until the seeds swell and soften. If after soaking the seed is still hard, scarification may be necessary to breach the seed coat.

If you are unsure about what process to do use to break physical dormancy, I recommend soaking

the seed first. If it swells and softens, you’re ready to plant. If not, then you can do a little rubbing on a nail file.

Check the Seed Packet!

Often specific germination requirements can be found on the seed packet. If you are unsure about an individual seed’s needs, and it’s not listed on the packet, visit the seed company’s website or do a search online.

Understanding how seeds germinate and what the specific requirements are for some seed will

go a long way to ensuring the successful germination of your garden seeds.

[…] Germinating seeds in a plastic bag is similar to the paper towel technique but offers added convenience for busy gardeners. This method works well for seeds that require high humidity to germinate. […]